*Note this story is in Cebuano

Mga 70 na ka tuig ang milabay sukad niadtong mga adlawa, lagmit labaw pa, apan kinsay ga-ihap? Usa lamang ako ka tigulang nga handumanan lamang intawon ang mao’y makapainit sa kasingkasing. Moinom ko para makahinumdom, muinom usab ako para makalimot.

Ang akong mga apo anaa sa sunod nga kwarto, kauban ang akong mga apo sa tuhod. Sa hilom nagpasalamat ko sa Ginoo sa akong maayong grasya. Nakahinumdom ko sa mga gabii’ng didto kami sa kampo sa mga POW, gisulod sa mga bagon ug walay bisan unsang paagi nga makita ang kalibutan sa gawas. Ginasipa sa mg Hapon ang kadaghanan kanamo matag bagon kada maka higayun sila. Nahinumdom ko sa mga kauban nako sa pakigdugmo, mga maayo’ng tawo sila. Nagapu sila sa sakit ug kagutom. Ambut kung giunsa nako paggawas didto nga buhi. Naubus niini ang tana’ng matang sa pisikal nga kusog nga akong maagwanta. Apan sa akong pagtan-aw sa mga mata sa akong mga anak ug sa ilang mga anak ug sa mga anak sa ilang mga anak, kahibalo ko nga ang akong gipakigbisogan takus sa tanan nga pag-antos nga akong giagwanta. Buhaton ko pa kini pag usab ug usa pa ka milyon ka beses.

Milingkod si Isa sa akong tapad ug nangutana kanako og dugang istorya. Sa tanan nako’ng mga apo sa tuhod mao kini siya ang alang nako labing maalamon. Kanunay’ng gatutuk ang iyang huna huna sa libro ug ganahan kaayo siya makadungog sa akong mga istorya, labi na kadto’ng gikan sa gubat. Karon, lahi ang akong isulti kaniya.

Usahay mobalik ko sa Lingayen. Ganahan kong mobarug sa bung-aw ug hinumdomon ang mga higala nga nakig-away uban kanako, ang mga higala nga nawala na kanako. Hilom na karon, apan mabatian gihapon nako ang nagpabiling lanog sa kamikaze nga eroplano nga naglupad didto padung sa mga barko. Sa miaging tuig wala ko nag-inusara. Ang akong mga mata dili na pareha kaniadto, apan kahibalo ko kung unsa kini gikan sa usa ka milya pa ang gilay-on.

Wala’y usa nga aduna’y panahon sa paglubong kaniadto. Malugutun kami ug amo’ng gigamit ug unsay anaa nga magamit. Kasagaran mao kini ang pagtabon sa mga lawas sa mga banig ug pagbilin niini sa dapit nga among kini’ng nakit-an samtang kami naglikay sa pagpabuto sa machine gun.

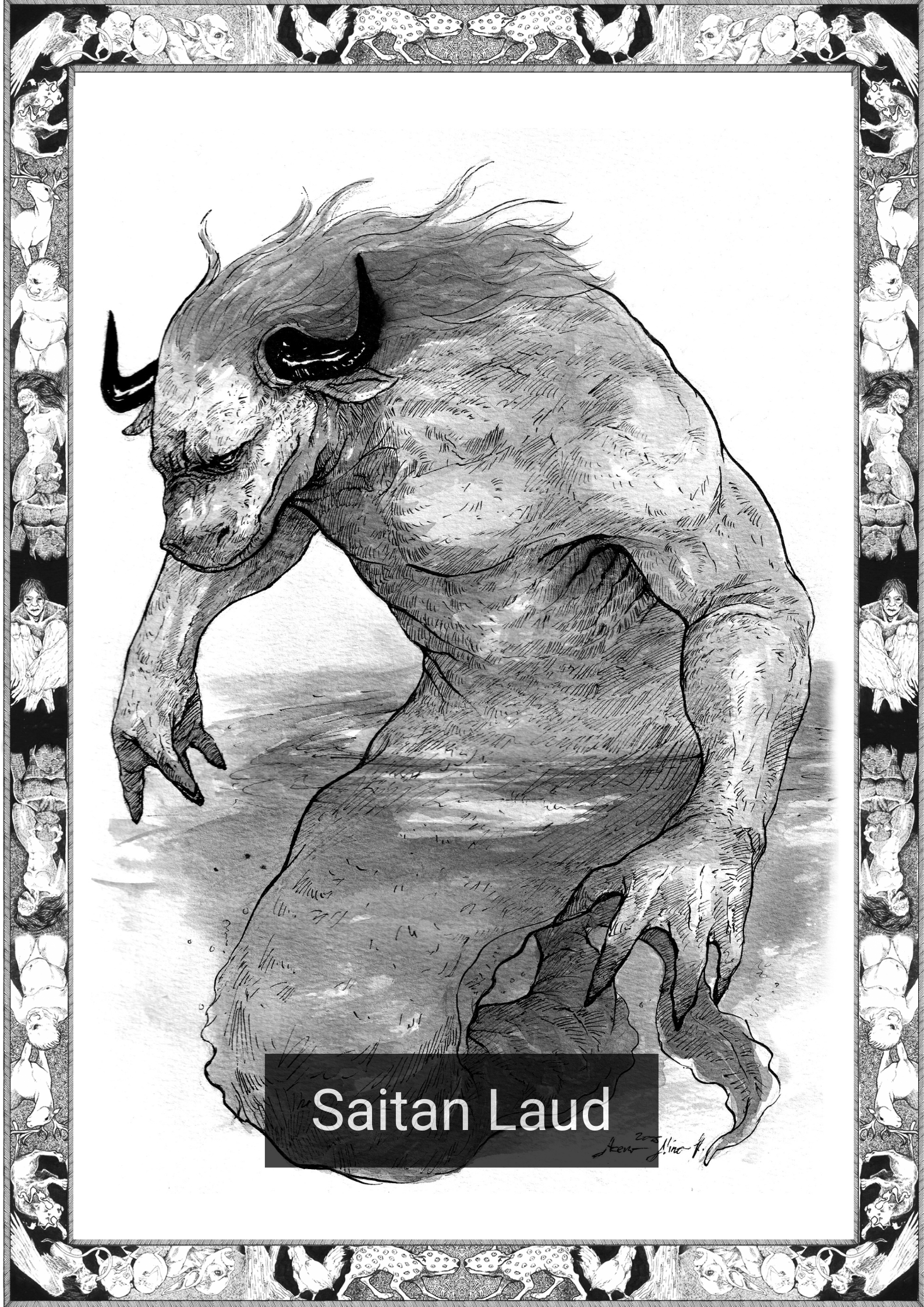

Nagtinan-away kami ug dugay. Wala ko kabalo kung nakaila ba ko niya, gikadugo ba nako siya o ako siya’ng gipadugo. Wala kini mutingog, wala gani mulihok. Nagbarog lang kini, nga nag-ali sa akong agianan. Gikuha nako ang kutsilyo nga regalo sa marine nga akong nahimamat pagkahuman sa gubat. Wala gyud ko maghunahuna nga nga manginahanglan ko pag gamit niini.

Gidunggab ko ang kalag sa iyang gibarogan, nahanaw ang mga bitiis niini ug mibukhad ang banig, nagpagawas sa makalilisang nga baho. Ang uban tawo lud-an gyud niining mao’ng baklag nga baho, apan sa tanan nakong naagian, nasayud ko nga usahay ang makalilisang nga baho makadala kanimo sa kagawasan.

Mikunot ang agtang ni Isa, sa akong hunahuna dili siya motuo sa akong mga pulong. Nangayo siyag lain sugilanon bahin sa mga kamikaze ug sa mga barko ug ako misurender na. Walay panaglalis sa usa ka bata nga nangita og istorya.

Mga 70 ka tuig na ang milabay sukad niadtong mga adlawa, apan ang mga kalag ug mga lanog nagpabilin gihapon.

=——————————————————=

English Version

About 70 years have passed since those days, probably more, but who’s counting? I’m just an old man who only has his memories to keep him warm. I drink to remember, I also drink to forget.

My grandchildren are in the next room, along with my great-grandchildren. I silently thank the Lord for my good grace. I remember the nights in the POW camp, stuffed in boxcars without any way to see the outside world. The Japanese would kick as many of us in each car as they could. I remember the men I fought with, good men. They were broken by disease and hunger. I don’t know how I got out of there alive. It took more than any sort of physical strength that I could ever bear. But looking into the eyes of my children and their children and their children’s children, I know what I was fighting for was worth all the suffering I could ever endure. I would do it again one million times over.

Isa sits next to me and asks me for another story. Among all my great-grandchildren I think she’s the smartest. She always has her head stuck in a book and she really likes hearing my stories, especially from the war. Today, I’m going to tell her something different.

I sometimes go back to Lingayen. I like to stand by the gulf and remember the friends that fought with me, the friends I had lost. It’s quiet now, but I can still hear the lingering echoes of the kamikaze aircraft flying into the ships. Last year I wasn’t alone. My eyes aren’t what they used to be, but I could recognize what it was from a mile away.

No one had time for burials then. We were resourceful and had to use what we could. That usually meant covering the bodies in mats and leaving them where we found them while we avoided machine gun fire.

We stared at each other for a long time. I don’t know if it was someone I knew, someone I bled with or someone I made bleed. It didn’t say a word, it didn’t even move. It just stood there, blocking my way. I took out the knife that was a gift from the marine I met after the war. I never thought I would have to use it.

I stabbed the ghost where it stood, its legs disappeared and the mat unfurled, releasing a horrible stench. To some people that putrid odor would be disgusting, but with all I’ve been through, I know that sometimes horrible smells can lead you to freedom.

Isa frowns, I don’t think she believes my words. She asks for another one about the kamikazes and the ships and I surrender. There’s no arguing with a young child looking for a story.

It has been around 70 years since those days, but the ghosts and echoes still linger.

————————–

*The Cebuano language, alternatively called Cebuan and also often colloquially albeit informally referred to by most of its speakers simply as Bisaya (“Visayan”, not to be confused with other Visayan languages nor Brunei Bisaya language), is an Austronesian regional language spoken in the Philippines by about 21 million people, mostly in Central Visayas, western parts of Eastern Visayas and most parts of Mindanao, most of whom belong to various Visayan ethnolingusitic groups, mainly the Cebuanos. It is the by far the most widely spoken of the Visayan languages, which are in turn part of wider the Philippine languages. The reference to the language as Bisaya is not encouraged anymore by linguists due to the many languages within the Visayan language group that may be confused with the term.

Written by Karl Gaverza

Cebuano Translation by Christine Rom

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

Translation Copyright © Christine Rom

Story inspired by the Pasatsat legends from Pangasinan.

Pasatsat Illustration by Leandro Geniston from Aklat ng mga Anito

FB: That Guy With A Pen

Watercolor by Isabel Leonio and Mykie Concepcion

Tumblr: http://