*Note this story is in Cebuano

Ang mga pag-antos nga gihatag sa mga linalang kaniadto dili mahanduraw. Bisan karon, madumduman gihapon nako ang mga sugilanon nga gisaysay sa akong lola, mga istorya sa pagpanimalus ug pagkawagtang. Nagapakita sila sa akong mga damgo.

Ug ang tanan nagsugod sa akong lolo.

Desidido siya nga maglampas kaniadto sa usa ka gamay’ng bahin sa bukid, aron iandam alang sa pagtanom. Wala ko masayod nganong gusto niya mag-uma ngadto sa ibabaw nga bahin sa bukid, layo sa iyang tipo nga lugar. Duol ang maong bukid sa bungtod nga ilang gitawag nga “lamesa”, ang halapad nga bato nga anaa sa ubos.

Gisunog ni Lolo ang kahoy nga anaa adtong lugara, ug niini nagsugod ang tanan nga kalbaryo.

Si Lola ug ang akong inahan miadto kaniya sa payag nianang gabhiuna aron dad-an siya ug panihapon. Didto na usab sila natulog. Ang makusog nga ngulob ug lagutob nga tunob sa kabayo ila pang nadumduman.

Sa padulong na sila matulog, sila gibati sa kahadlok sa maong tingog nga naglibot sa gamay’ng payag.

“Benito, guwa diri! Makig-estorya ako kanimo.” Ang tingog sa akong inahan ug lola samtang gi-imitar ang tingog sa maong linalang matag higayon nga ila isaysay ang istorya, pero matud pa kanila, dili gyud nila masundog ang maong tingog. “Aduna’y kaligutgot sa kasingkasing ang tingog niini,” ingon nila, “labaw pa kini sa among masundog.”

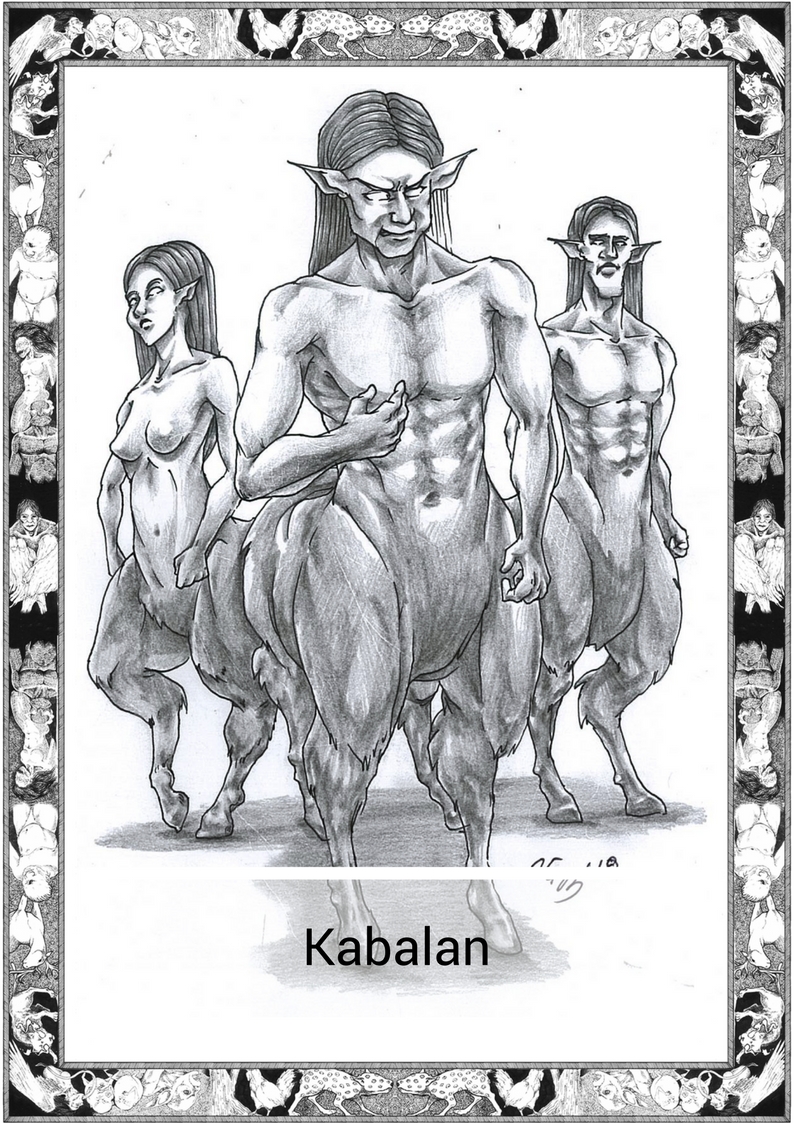

“Hayag kaayo ang buwan niadtong taknaa.” Mao kini ang bahin sa istorya diin gisaysay ni lola ang mahitungod sa linalang. “Tawo sila gikan sa ulo ngadto sa tiyan, apan kabayo sa tiyan paingon sa ilang tiil.” Ug nahinumdom ako sa mga nagkalain-laing istorya sa bisan asang bahin sa kalibutan, diin ang mga linalang nga katunga-tawo ug katunga-kabayo nagatabang sa mga tawo sa dugay nang panahon.

Ingon ni lola nga ang mga espiritu kaniadto dili makatabang sa bisan unsa. Niabot lamang sila para makapanimalos sa mga katawhan.

“Bayari ang imong pagkasumat ug kawalay pagtagad.” Nasuko nga gitudlo sa lider sa mga Kabalan ang akong lolo. Gisaysay niini nga gipatay sa akong lolo ang iyang igsoon dihang gisunog niya ang usa ka kahoy. Nahadlok ang akong lolo ug nagpakilooy sa maong linalang nga dili siya pagpatyon. Wala unta niya masunog ang maong kahoy kung nakahibalo lamang siya nga adunay nagpuyo niini.

Wala panumbalinga sa linalang ang sagmuyo sa akong lolo.

Ug didto nagsugod ang tanang kalbaryo. Nilakaw ang mga linalang niadtong gabhiuna apan ang ilang sumpa nagpabilin. Bisan ang mga doctor wala masayod unsa matuod nga sakit sa akong lolo. Nihunong siya pagkaon kay sa matagtulon niya sa kan-on, muubo ug musuka siya ug dugo. Matud niya, daw mura ba ug masunog sa kainit ang iyang tutunlan kada suka.

Wala nay lain nabuhat si lola, miduol siya sa albularyo, ang among lokal nga mananambal. Gihangyo pag-ayo sa mananambal ang maong linalang. Miingon ang akong lola nianang gabhiuna sa manalagna nga magbuhat og laing ritwal sa sunod nga gabie, apan ang tanan nahimong way pulos.

Ang mga linalang wala manumbaling.

Human mamatay ang akong lolo, naigo sa kilat ang igsoong lalaki sa akong inahan samtang kini nisaka sa lubi kilid sa ilang balay. Milabay pa ang tulo katuig ayha kini nipanaw samtang kini natulog.

Ang pamilya sa akong inahan nawad-an og kadaghanan sa ilang mga kabtangan ug gikapiutan sa kalisod hangtud nga namatay ang akong lola tungod sa kanser.

Ang mga linalang dili kahibaw ug unsay kalooy, para kanila, ang pagpanimalos lamang ang paagi hangtod nga mabayaran ang tanang kasal-anan nga nabuhat pinaagi sa dugo.

=———————=

English Version

The tragedies that these creatures bring are unimaginable to some. I still remember the stories that my lola used to tell, stories of vengeance and loss. They follow me in my nightmares.

It all started with my lolo. He decided to kaingin a small piece of land in the mountains, to prepare it for the planting season. I don’t know why he decided to go further up the mountain, away from his usual spot. It was near the waterfall they called “lamesa”, relating to the flat rock on the bottom.

He burned the tree that was there and that was the start of the troubles.

My lola and mother joined him in the payag (nipa hut) afterwards to bring him dinner and to spend the night with him. They still remember the loud hoofbeats. The feeling of dread when the sound circled their small hut still echoes in their memories before they sleep at night.

“Benito, come out. We need to talk to you.” My mother and lola tried to replicate the voice every time they told the story, but they said they could never get it right. “There was too much anger in the voice,“ they said, “more than we can mimic.”

“The moonlight was bright that night.” This was the part of the story where lola describes the creatures. “They were human from head to trunk, but were horses from their trunk to their feet.” I thought back to myths from a different part of the world, where half-human half-horse beings would help humankind. Lola told me that these spirits weren’t helpful at all. They came seeking vengeance.

“You will pay for such arrogance and disrespect.” The leader of the kabalans pointed to my lolo. It told him that my lolo killed its brother when he burned his tree. My lolo begged for his life. He would not have burned the tree had he known there was something living there.

The creatures didn’t care.

Thus began the tragedy. The creatures left that night but their curse lingered. Doctors were never able to tell what exactly was wrong with my lolo. He stopped eating because every time he ate he would vomit and cough up blood. He said it would burn his throat every time he vomited.

My lola had no other choice, she consulted the manggagamot, our local faith healer. The faith healer tried to reason with the creatures. My lola said that night after night the faith healer would try another ritual, but it was all for naught.

The creatures would not be appeased.

After my lolo died, my mom’s elder brother was struck by lightning while he was at the top of the coconut tree outside their house. After three years he died in his sleep.

My mother’s family lost most of their properties and were trapped in poverty until lola died of cancer.

These creatures don’t know the meaning of mercy, they will seek their vengeance until they are repaid in blood.

Beware the kabalans, for they will not listen to your pleas of forgiveness. And be careful around the trees high up in the mountains, you will never know if one makes its home there, not until it’s too late.

=————————=

*The Cebuano language, alternatively called Cebuan and also often colloquially albeit informally referred to by most of its speakers simply as Bisaya (“Visayan”, not to be confused with other Visayan languages nor Brunei Bisaya language), is an Austronesian regional language spoken in the Philippines by about 21 million people, mostly in Central Visayas, western parts of Eastern Visayas and most parts of Mindanao, most of whom belong to various Visayan ethnolingusitic groups, mainly the Cebuanos. It is the by far the most widely spoken of the Visayan languages, which are in turn part of wider the Philippine languages. The reference to the language as Bisaya is not encouraged anymore by linguists due to the many languages within the Visayan language group that may be confused with the term.

Written by Karl Gaverza

Cebuano Translation by Anelyne Ruflo

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

Translation Copyright © Anelyne Ruflo

Adapted from a Story told by Grace Collantes

Kabalan Illustration by Ysa Peñas

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/