*Note this story is in Cebuano.

Gilikayan ni Aguihao ang panan-aw sa mumbaki* samtang nagkupot sa panapton nga nagtabon sa iyang tuong bukton.

“Kaisog gud nimong moanhi nako aron mangayo og pasaylo sa espiritu,” miingon ang mumbaki samtang nagtan-aw sa bukton ni Aguihao.

“Gibuhat nako ang kinahanglan nakong buhaton alang sa akong pamilya,” tubag ni Aguihao, nga gipalabi ang pagtan-aw sa yuta kaysa pag tan aw sa mumbaki nga mata sa mata.

“Imo’ng giyurakan ang mga tradisyon sa among mga katigulangan! Mao na ni ang paagi sa amo’ng kinabuhi sulod sa mga henerasyon ug mangahas ka sa pagkuwestiyon niini?!”

“Wala ka kasabot! Wala ka kahibalo kung unsa ka ka swerte nga gitugotan ang mga espiritu nga mosulti pinaagi kanimo samtang ang mga sama kanako kinahanglan nga maghago adlaw-adlaw tungod sa imong ‘mga balaod’.”

“Kana’ng mga balaod gidumala sa mga espiritu, ang pagsupak niini mao ang pagsupak sa kapalaran.”

“Tingali ang imong kapalaran, apan dili ang ako.”

Usa ka kalit nga kahilom ang mipuno sa hangin ug gibuak kni sa mumbaki.

“Hubua na,” mando niya kang Aguihao.

Ang mga lut-od sa panapton mipagawas sa usa ka nihubag nga samad nga nagtulo ug nana. Ang nawong ni Aguihao halos dili makatago sa kasakit ug sa unang higayon mitan-aw siya sa mga mata sa mumbaki. Adunay kaluoy didto ug gamay nga pagmahay.

“Isulti kanako ang imong istorya,” miingon ang mumbaki.

“Nagsugod kini sa pagkamatay sa akong asawa.”

“Nahinumdom ko niana. Mitambong ang mombangol**.”

“Oo, ug wala na nako ang tanan. Gikiinahanglan nakong iprenda ang akong kabtangan aron makakuha ang ug panggasto para sa lamay.”

“Kitang tanan kinahanglang mosunod sa mga ritwal. Sulod sa lima ka adlaw ang mga baboy ug mga kabaw kinahanglang ihalad ngadto sa mga diyos ug mga spiritu.”

“Dili makatarunganon ang pagkuha gikan sa mga uyamut nga wala’y bisan unsa.”

“Imortal ang kalag. Kinahanglan natong buhaton ang tanan nga atong mahimo aron masiguro nga makaplagan niini ang dapit niini sa kinabuhi human niining kinabuhia.”

“Sa sulod sa lima ka adlaw gilamayan namo siya ug gipalingkod sa handel***.”

“Ug nahimo nimo ang kinahanglan nimong buhaton base sa atong mga tradisyon.”

“Apan dili kini patas! Mas nisamut pa ko ka uyamut kaysa kaniadto.”

“Dili lang kini bahin sa lamay, dili ba?”

“Dili, dili.”

“Isulti kanako ang uban pa sa imong istorya.”

“Ako ang ikalima nga anak sa akong mga ginikanan. Sila walay kakapoy nga nagtrabaho aron makapundar ug kabtangan alang sa ilang mga anak ug bisan sa ilang mga giagiang pagsulay nakatigom sila og lima ka humayan ug kalasangan. Sa dihang kaslon na ang akong magulang nga lalaki, nakuha niya ang katunga sa tulo ka bahin sa propiedad. Ug ang uban gibahin sa akong kamagulangang babaye ug sa akong usa pa ka igsoon nga lalaki. Gihatag pa gani nila sa akong kamagulangang igsoong babaye ang balay sa pamilya. Wala nay nabilin pa sa nahabilin kanamo.

“Miyatak ka sa peligrosong lugar. Ang pagpangutana niini mao ang paglihok batok sa panaghiusa. Ang kahigayonan sa usa ka tawo sa kinabuhi usa lamang ka gamay nga sakripisyo aron maseguro nga ang mga tradisyon masunod.”

“Aduna ko’y utang nga mosunod kanako hangtod sa akong kamatayon, nga masunod usab sa akong mga anak ug ilang mga anak. Gibuhat nako ang akong mahimo aron mahatagan sila ug higayon. ”

“Mao ba kana ang hinungdan nga miadto ka sa balay sa imong igsoon?”

“Daghan kaayo siya’y iya, dili na niya mamatikdan kung mawalaan siya sa uban niyang kwarta. Nagkinahanglan lang ko og gamay nga kantidad.”

“Ug unya gidakop ka sa espiritu.”

“Wala ko kahibalo nga ang akong igsoong lalaki adunay espiritu nga may tigpanalipod sa iyang mga butang.”

“Mosulay ka ba sa pagpangawat kon nahibal-an nimo?”

“Oo. Kung alang lang sa akong pamilya.”

Laing kahilom ang mipuno sa lawak, apan niining higayona si Aguihao na ang mibuak niini.

“Adto sa ko, mumbaki. Nakita nako sa imong mga mata nga nakalapas ko dili lang sa kabtangan sa akong igsoon kon dili sa mga tradisyon usab sa among tribo. Sobra na kaayo ang pagpangayo og pasaylo alang sa duha, ug kini ang akong penitensiya.”

Samtang nagbarog si Aguihao aron molakaw palayo, giisa sa mumbaki ang iyang kamot.

“Huwat sa,” singgit sa mumbaki.

“Buhaton ba nimo ang ritwal?” pangutana ni Aguihao.

“Nasayod ka ba nga usa ako sa kataposang mumbaki sa atong mga probinsiya?”

“Nakadungog ko nga nagkagamay ang mga tawo nga nagkupot sa kupo sa mumbaki.”

“Tingali kini ang timaan sa mga panahon, o tingali ang mga espiritu wala na magtugot sa ilang kaugalingon nga madungog. Himalatyon na ang karaang mga paagi, Aguihao. Ang mga batan-on mas gusto nga adunay usa ka piraso nga papel nga nag-ingon nga sila ‘edukado’ kaysa mopasalig sa pagkat-on sa mga pag-ampo ug pag-awit sa atong mga tawo. Nakigsulti sila sa ilang diyos nga adunay tulo ka kinaiya sa usa ug nagsimba sa mga templo nga bato.

“Ila bang sala? Unsa may nahibilin alang kanato dinhi?”

“Tingali mobati ka nga wala dinhi, apan ang mga espiritu labing kusog nga mulanog sa kahilom.”

Mibarog ang mumbaki ug mikupot sa bukton ni Aguihao.

“Sa pagkakaron, magkinahanglan kami og manok.”

*Mumbaki/Mombaki mao ang Babaylan sa kultura sa mga Ifugao

**Ang labaw sa nga mumbaki.

***Lingkuranan nga gihimo sa ilawom sa balay

=——————————————————-=

English Version

Aguihao avoids the gaze of the mumbaki* as he clutches the fabric covering his right arm.

“I am amused by the nerve you have coming to me to ask for the spirit’s forgiveness,” the mumbaki says as he looks at Aguihao’s arm.

“I did what I needed to do for my family,” Aguihao answers, preferring to look at the ground than meet the mumbaki eye to eye.

“You spit on the traditions of our ancestors! This is the way we have lived for generations and you dare question this?!”

“You don’t understand! You don’t know how lucky you are to let the spirits speak through you while those like me have to toil day after day because of your ‘laws’.”

“Those laws are governed by the spirits, to go against them is to go against destiny.”

“Your destiny maybe, but not mine.”

A pang of silence fills the air and is broken by the mumbaki.

“Take it off,” he commands Aguihao.

The layers of fabric give way to a swollen wound leaking pus. Aguihao’s face barely hides the pain and for the first time looks into the mumbaki’s eyes. There is pity there and a small twinge of regret.

“Tell me your story,” said the mumbaki.

“It started with the death of my wife.”

“I remember that. The mombangol** attended.”

“Yes, and I lost everything. I had to mortgage my property to find the funds for the vigil.”

“We all must follow the rituals. For five days pigs and carabaos must be offered to the gods and spirits.”

“It makes no sense to take from those who have nothing.”

“The soul is immortal. We must do all we can to make sure it finds its place in the life after this life.”

“For those five days we mourned her and sat her upon the hangdel***.”

“And you have done as you must do based on our traditions.”

“But it’s not fair! I have even less than what I had before.”

“This is not just about the vigil is it?”

“No, it is not.”

“Tell me the rest of your story.”

“I am the fifth child of my parents. They had worked tirelessly to save property for their children and through their trials they had accumulated five rice fields and forests. When my older brother was to be married, he got one half of three fourths of the property. And the rest was divided among my eldest sister and my other brother. They even gave my eldest sister the family home. The rest of us were left with nothing.”

“You tread on dangerous ground. Questioning this is acting against unity. One’s chance in life is but a small sacrifice to ensure that the traditions are upheld.”

“I am in a debt that will follow me until I die, that my children and their children will inherit. I did what I could to give them a chance.”

“Is that why you went to your brother’s house?”

“He has so much, he wouldn’t notice some money missing. I just needed a small amount.”

“And then the spirit caught you.”

“I did not know that my brother had the spirit invoked to protect his belongings.”

“Would you have tried to steal had you known?”

“Yes. If only for my family.”

Another spate of silence filled the room, but this time it was Aguihao that broke it.

“Goodbye, mumbaki. I can see it in your eyes that I have trespassed not only on my brother’s property but also on the traditions of our tribe. It is much too much to ask forgiveness for both, and this would be my penance.”

As Aguihao stood to walk away the mumbaki raised his hand.

“Stay,” the mumbaki intoned.

“Will you do the ritual then?” Aguihao asked.

“Do you know I am one of the last mumbaki among our provinces?”

“I have heard that less and less people were taking up the mantle of the mumbaki.”

“It may be the sign of the times, or maybe the spirits aren’t letting themselves be heard. The old ways are dying Aguihao. The young would rather have a piece of paper that says they are ‘educated’ than committing to learning the prayers and chants of our people. They speak to their god with three natures in one and worship in stone temples.”

“Is it their fault? What is there that is left for us here?”

“You may feel that there is nothing here, but the spirits echo loudest in the silence.”

The mumbaki stands up and clutches Aguihao’s arm.

“For now, we will need a chicken.”

=————————————————————–=

*Mumbaki/Mombaki are shamans in Ifugao culture.

**The chief mumbaki.

***An improvised chair constructed under the house.

=—————————————————=

*The Cebuano language, alternatively called Cebuan and also often colloquially albeit informally referred to by most of its speakers simply as Bisaya (“Visayan”, not to be confused with other Visayan languages nor Brunei Bisaya language), is an Austronesian regional language spoken in the Philippines by about 21 million people, mostly in Central Visayas, western parts of Eastern Visayas and most parts of Mindanao, most of whom belong to various Visayan ethnolingusitic groups, mainly the Cebuanos. It is the by far the most widely spoken of the Visayan languages, which are in turn part of wider the Philippine languages. The reference to the language as Bisaya is not encouraged anymore by linguists due to the many languages within the Visayan language group that may be confused with the term.

Written by Karl Gaverza

Cebuano Translation by Christine Rom

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

Translation Copyright © Christine Rom

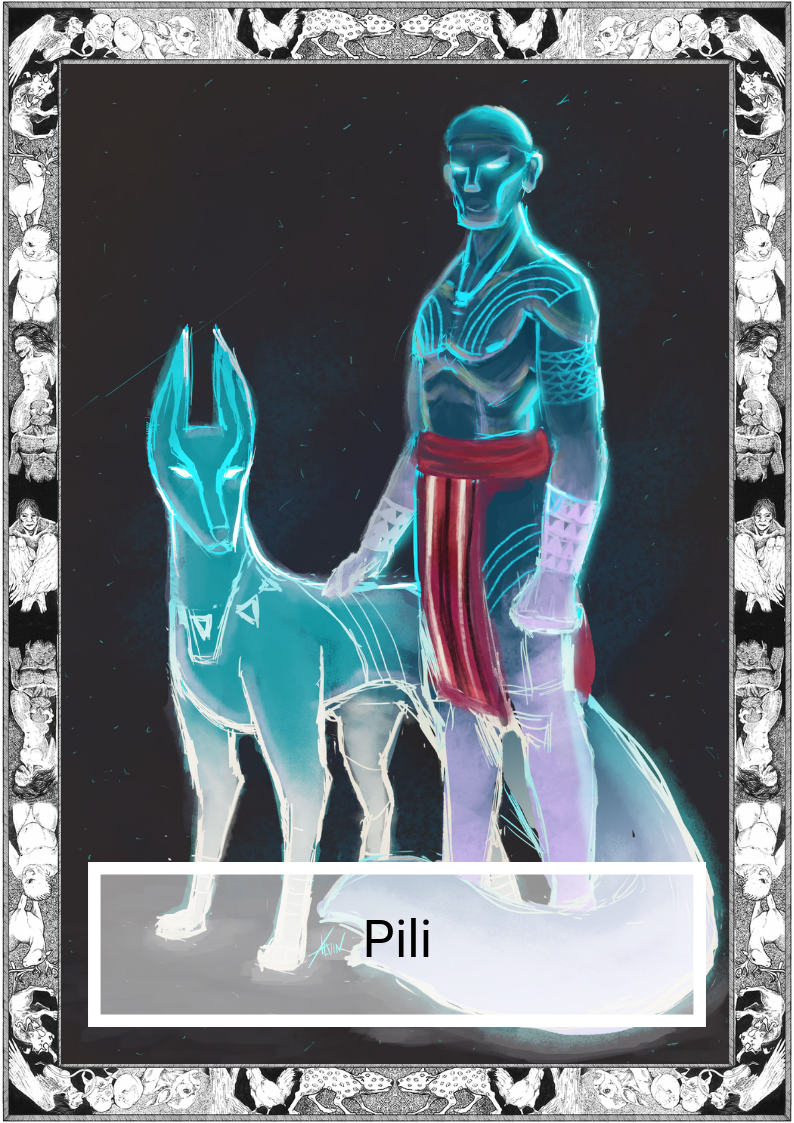

Inspired by the Pili description in Gibson’s Sacrifice and Sharing in the Philippine Highlands (London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology,n.57); The Athlone Press: London, UK, 1986.

Pili Illustration by Alvin Gasga

FB: The Art of Alvin Gasga