(1994) Nichter, M. Anthropological approaches to the study of ethnomedicine. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers.

Wait, no, that isn’t right.

Nichter, M. (1994). Anthropological approaches to the study of ethnomedicine. Amsterdam: Gordon and Breach Science Publishers.

Goddamned citation formats. I always forget if the date goes before or after the author.

I let out a loud sigh (okay maybe a grunt) and everyone in the coffee shop stares.

I also forget when I’m in public.

I sink into my chair and hope that the rest of the shop goes on about their day.

Whatever. This paper’s going nowhere. Why the hell did I choose healing rituals as my topic for this anthropology class. I could’ve been in a bar somewhere interviewing people about their body modifications but no, I had to get dengue and think about how indigenous people dealt with sickness.

Now I’m in a coffee shop staring at a Wikipedia article about the history of medicine in the Philippines and wondering how I can find more information on the similarities between traditional Chinese medicine and native Filipino medicine.

Another sigh escapes me, but this time it’s a lot quieter. I’m certain no one heard it.

No one except her.

She was a small woman, about my height, with nut-brown skin and curly hair. She asked if she could sit with me (it was then I noticed that there were no free chairs in the shop) and I said yes.

The irritation on my face must have been obvious because she asked if I was okay. I gave a soft chuckle and explained that today wasn’t my day.

The paper (that was 40% of my final grade by the way) was a hurdle that I didn’t know how to jump. There were just so many variables. Do I list down all the different methods of folk medicine around the country? Do I just limit it to a certain area? Do I just focus on herbal remedies? What about modern practices that were amalgamations of indigenous rituals and foreign influence (hence the Wikipedia article)?

The woman smiles at me and quietly asks me to calm down. The tranquility in her voice washes over me and switches my mind from erratic racing to soothing stillness.

I lean back into my chair and apologize to the woman. The paper’s my problem, not hers. No sense in letting the stress spill over to other people.

She tells me that the life of a university student isn’t easy and it’s perfectly normal to feel out of control.

I thank her and offer to buy her a cup of coffee (or tea). It’s rare to find someone that understands what you’re going through and won’t use it against you.

She declines my offer and instead asks me about my paper.

I tell her there isn’t much to say. About a month ago I was in the hospital fighting for my life. Between the fever, the blood transfusions and the big white room I called home, something struck me – What if I didn’t have this hospital? What would happen if I was in the middle of the province, unable to leave the house? Without western medicine, how could you cope?

And that was it. As soon as I was well enough to go back to school (facing a mountain of work I had to finish) I made a decision. I took incompletes in all my classes except one: Anthropology. I figured I could convince my prof to let me use this as the topic for my final paper.

It seemed like a good idea then. Now is another matter.

Instead of nodding her head and changing the topic (like I expected), she actually seems interested in what I have to say.

So, I ask her what I should do.

Her brow furrows and she takes a minute to reply. She asks me where I’m from.

I tell her I’m a city girl, born and raised in Makati.

She corrects herself and asks me where my family is from.

As far as I know my parents are both from Negros. My dad is from Bacolod and my mom is from a place called Tanjay in Negros Oriental.

Her eyes light up when I mention Negros. She says she’s from there as well. In a city north of Tanjay called Bais.

The coincidence surprises me. It was a welcome distraction from my paper, but time’s growing short and I tell her that I have to get back to writing.

She tells me that maybe she has something that could help. We agree to meet at this coffee shop at the same time tomorrow. I’m not sure what’s going to happen, but curiosity compels me.

I let a day pass, order a large Americano, and settle in my usual spot.

And just as promised, she’s at the coffee shop like clockwork.

She tells me she can’t stay and she was only here to give me something: an old book. As she leaves, she says that maybe I should research something closer to home and to check page 419.

I don’t even get a chance to say my goodbye so I sit back down and leaf through the pages.

Studies in Philippine Anthropology (In Honor of H. Otley Beyer) – Edited by Mario D. Zamora (Associate Professor and Chairman, Department of Anthropology). Copyright 1967 – Alemar-Phoenix Publishing House.

I recognize the name Beyer – he was an American anthropologist that spent most of his life dealing with Philippine indigenous cultures. At the very least this seems legitimate because of his name.

Flipping to page 419, I’m met with the title: The Bais Forest Preserve Negritos: Some Notes On Their Rituals and Ceremonials by Timoteo S. Oracion – Silliman University.

She was right, this was much closer to home.

The study is about 20 pages long and it’s perfect. There are nearly a dozen rituals cataloged, 6 of them about sickness. If she had stayed, I would’ve given her the biggest hug. This is just what my paper needed.

Going through the rituals is easy (the author made them very clear) and my fingers dance on my keyboard until all 30 pages of the paper is done.

I do my due diligence and edit the paper, making sure the citations are correct and fixing any spelling errors. And one part catches my eye – the Daga or Dolot ceremony.

It is a ritual for those that had just recovered from sickness. Varieties of food are prepared: beko, a sticky rice cooked with sugar and coconut milk (Biko in other words); dinogo-an, pigs blood stew with its internal organs (dinuguan’s my favorite); a rice cake called bodbod (the internet tells me that it’s like suman); rice, liquor cigarettes and tuba.The tambalan (or babaylan) recites a few words, waiting for the spirits to arrive and dances the sinulog (which I guess is more than the festival). The tambalan continues this until they are exhausted at which point they pick up bits of food and places them on empty plates on the ground. When all the plates have been filled the tambalan signals to the owner of the house to bring the rice and the people gathered have a feast.

I wish they had something like that after I beat dengue.

I turn in the paper and I score an uno (1 is the highest grade you can get). I feel a sense of relief that it’s finally over, though it’s weighed down by something.

I never saw the woman again. Whenever I stop by the coffee shop, I ask the baristas if they’ve seen her and they always say no.

That leads me to tonight. I don’t know what compelled me to do this, but it just seems right.

My dining room table is filled with biko, dinuguan, suman, rice and some tuba. I’m going to tell my family that it’s a surprise dinner for them, but before I let them in, I have to say:

Bulalakao sa kabukiran

(Falling stars from the mountains)

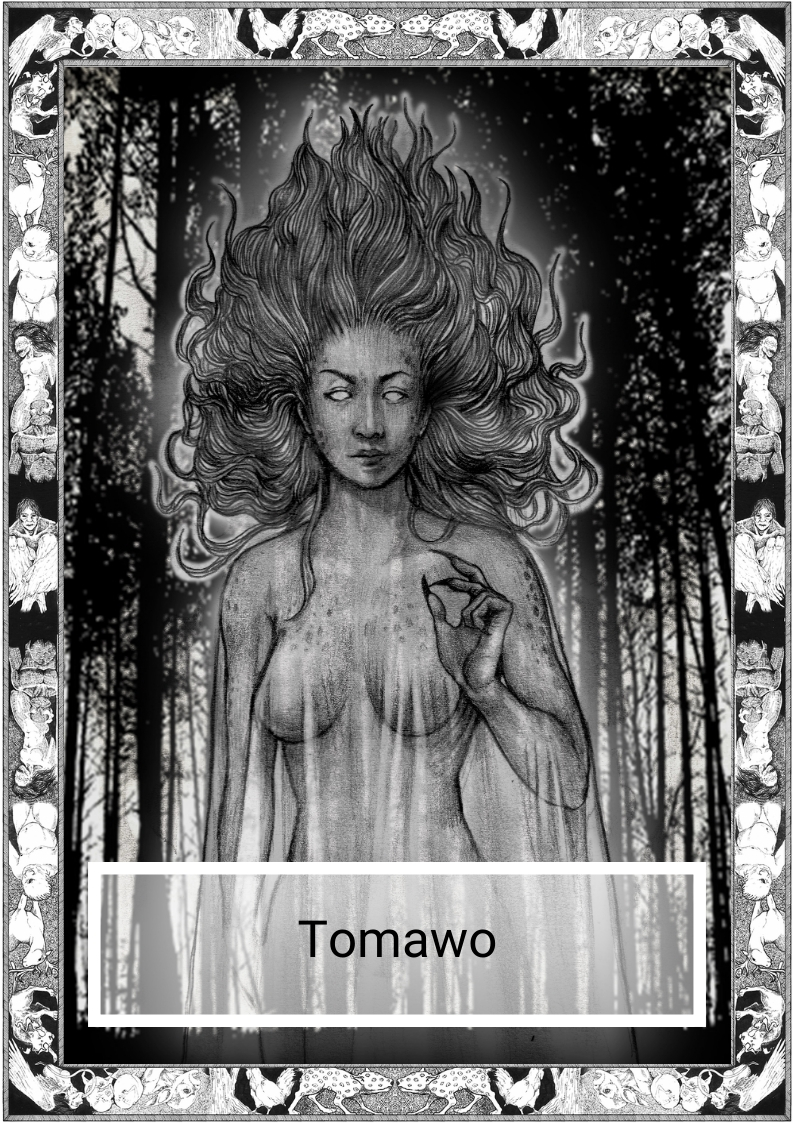

Mga tomawo sa talon

(Supernaturals from the other side)

Sa amihanan, sa habagatan,

(From north, from south)

Palapit na kamo yari ang pagkaon

(Come nearer all of you, here is food)

Guina dolot namon sa inyo

(We offered for you)

Written by Karl Gaverza

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

Inspired by The Bais Forest Preserve Negritos: Some Notes On Their Rituals and Ceremonials by Timoteo S. Oracion in Studies in Philippine Anthropology (In Honor of H. Otley Beyer)

Tomawo Illustration by Abe Joncel Guevarra

FB: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100008285862780