The year was 1946, a year after the Americans helped liberate my province from the grip of the Japanese. We Aklanons are a strong people, and we kept our heads down as we rebuilt from the ashes of the great war. Those were quiet years, the guerillas traded their guns for farming tools and everyone so desperately wanted to return to a sense of normalcy.

There were things that didn’t make sense to me at the time. There were many that were sick and dying, still a year after the war. Food was hard to come by and we did what we could to survive. The older members of the community, or what was left of them would stay up at night with a stingray tail in their hands. I was only a child then, and they didn’t think it was important to tell me what they were doing.

If I could I would thank them for that. There were times I wish I could resurrect my innocence, live in bliss unaware of how things really were.

I didn’t know why they needed garlic, salt and vinegar, or why only those with long loosed hair would keep watch. It didn’t even cross my mind why the bodies kept on piling up even after the war. I just remember being so hungry I would do anything for food.

My older brother did what he could to help. We lost our parents in the war and it was up to him to feed the other four members of his family. He would spend the whole day finding odd jobs around the area to scrounge up enough money for our meals. He died last year, and I don’t think I ever told him how thankful I was that he was there for me. It’s one of the great regrets of my life.

Some nights he would return as late as midnight. I always stayed up to make sure he got home safe. I was the second eldest and even though I was young then, I knew if he was gone I would have to take on a heavy burden on my shoulders.

One night he went back home with tears in his eyes. There were wounds on his arms that he washed and bandaged when he got home. I tried to ask him what happened but he wouldn’t answer. Through the years I would try to bring up the topic, my curiosity burning bright in my young mind, but my brother remained evasive.

It was only years later that I learned about the hunched man.

It seemed in our small village that people were dying even after the war. The ravages of famine spared no one in our community, but there were those that simply disappeared from our small town. The elders tried to caution us, but what could they say? After the war those that were left had to make sure there was a life still worth living.

Many of us left for greener pastures, those that stayed farmed the blood-soaked earth praying that something good would grow.

I don’t remember what I thought of it then. My young mind probably imagined that they all left because they couldn’t stand the painful memories of war.

But the truth was so much stranger.

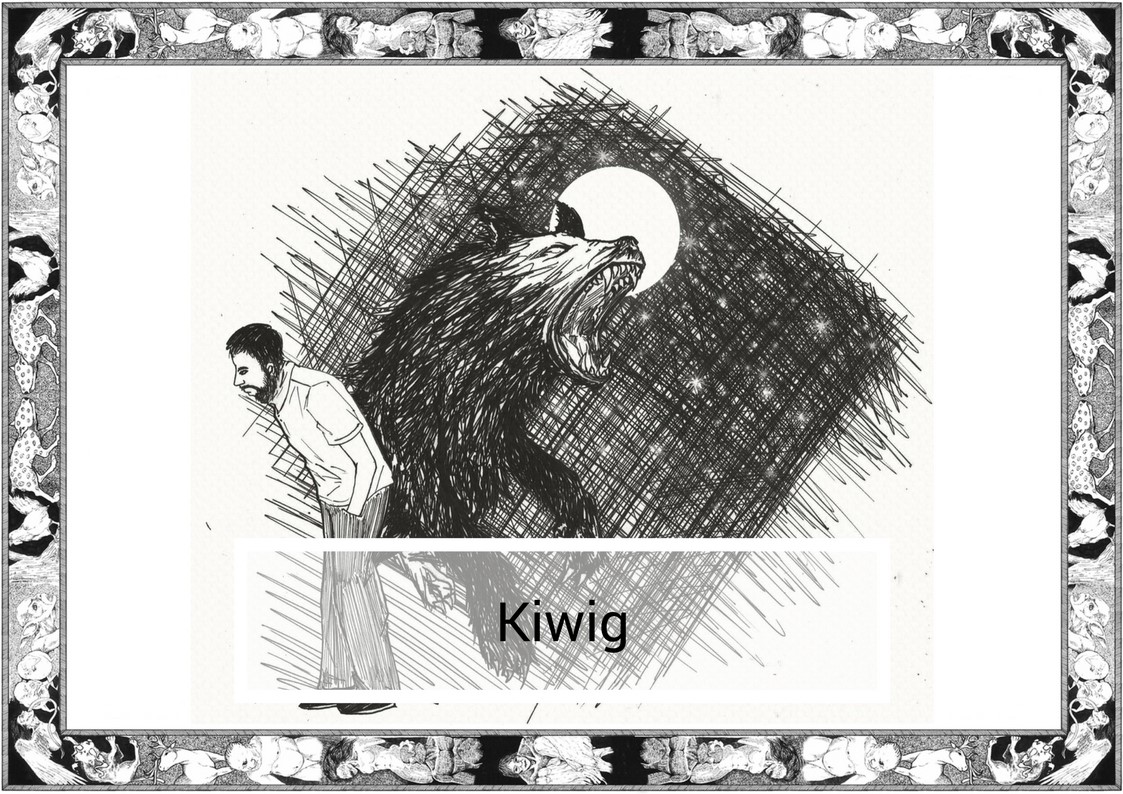

I am 92 years old now and I still shudder when I remember the hunched man. How he would wait outside your house, late at night and in the morning, you would disappear. How he would change into a great beast with eyes like fire and fur as matted as rattan. How it would only take seconds before a single bite would separate you from the rest of your life.

The hunched man does not bother us anymore. Maybe he left when the harvests started to sustain us, I don’t know.

But I tell this to my grandchildren every night. Always bring garlic, salt and ash. Always keep your hair long and loosed and carry a stingray tail.

For you never know when the hunched man will stay by your door.

Waiting for his moment to strike.

————————–

Written by Karl Gaverza

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

Inspired by the Kiwig description in 101 Kagila-gilalas na Nilalang. Samar. 2015

Kiwig Illustration by Jowee Aguinaldo.