There are 41 possible different species of venomous snakes in the Philippines. Of that number 26 are sea snakes and the other 15 are terrestrial snakes that live in diverse habitats in freshwater and on land. Some species like Tropidolaemus subannulatus are arboreal and almost never go down to the ground. All terrestrial species of these are able to swim and some inhabit areas near human habitation, around sources of water such as flooded rice fields, streams and rivers, and in agricultural areas.

Venomous snakes in the Philippines are represented by two families: Elapidae and Viperidae while there also occur mildly venomous snakes which are members of the family Colubridae. It is still up to future research to determine the degree of danger that these mildly venomous snakes pose to humans.

It may be hard to distinguish venomous from non-venomous snakes without special attention to detail. Several snakes in the Philippines are black with white bandings and these include the species Calmaria lumbricoidea, Lycodon subcinctus, and members of the genera Hemibungarus and Calliophis. The latter two are dangerously venomous while the other species are non-venomous. The only way to tell the difference is to check the side of the head in front of the eye to see if a loreal scale is present. If there is no loreal scale then the snake in question may be venomous.

In the Philippines, the snake fauna is relatively well known, but there are areas such as those in Luzon, Palawan and Mindanao that have not been explored in detail. It should be noted that accurate knowledge of snake species is necessary for proper treatment of snakebites. For example, there is only one antivenin manufactured for cobra snakebites derived from the species Naja philippinensis. It was believed in the past that there was only one species with three subspecies of the Philippine cobra, Naja naja, but further research has shown that the three subspecies are distinct and have been recognized as full species. This is important to note because antivenin is species specific, the antivenin used for one kind of snakebite may not work for bites of other species.

Her hands drifted across the keyboard and she took another sip of coffee. This should be good enough for now. The introduction is always the hardest part, then the rest just flows.

She stood up and went to her bag and took out some pictures. “Lovely,” she said to no one in particular. It had taken her months of work, traversing mountains and islands to get this collection. It was her life’s work, but she knew she had to do so much more.

The first picture was of Ophiophagus Hannah, also known as the king cobra. She knew how to describe every part of the snake’s anatomy. Her fingers ran through the nasal scales and noted that the loreal scale was absent.

She flipped through the pictures and picked another one at random. This time it was of Trimeresurus (Parias) schultzei, a green-turquoise snake with alternating bands of black and red. She remembered seeing this species in her travels to Leyte and Samar. They were tree-dwelling and it took her many attempts to get a proper photograph.

Laughter filled her small room. Such wonder and majesty that the elders of her people just ignored. There was power in knowing what you could conjure and they just wasted it on petty cantrips and dime store illusions.

Not her. Never her.

When the elders held her initiation, she did not fear. She had seen the kind of power that their kind possessed. Large black dogs, grotesque flying beings, flaming phantasms were but some of the conjurations she had experienced. But what she remembered was the snakes.

It was the favorite illusion of their people. A gnarled mass of slithering serpents flung at their victims, most of which died of fright in an instant. Those that were left alive through small mercies would forever have nightmares of the forked tongues, limbless bodies and scaled skin.

But the elders had no imagination. They assumed that all snakes looked like pythons and left it at that. It would end with her. She would show them all what they could be capable of if they just tried to see the horror that was at their doorsteps.

From the corner of her eye she could see the familiar black rings of the Hemibungarus calligaster, known by some as the Philippine coral snake. She held the photo against her chest and a faint orange and black glow manifested from her hands. In a moment the black and white ringed serpent was in front of her. She savored the beauty of her creation. This one she had seen in her hometown in Quezon province and it was this very snake that lead her heart to wander through the archipelago. She thanked it silently and went back to her research.

She had learned a lot from libraries and forests. Leafing through books and finding the creature in real life was a thrill she could never let go of. But there were other sources that she had queried, at a price.

Her mind drifted to Iloilo. There was a woman there with power much like hers, but different. She wouldn’t make eye contact for fear she would be exposed, but it was no use. She needed to know. The scar on her palm was throbbing now, the memories made her mind relive the pain. It was worth it though, she got what she was looking for.

The serpent that she would master.

Again, there was laughter. This would be no mere snake, no earthly beast. She walked to the window and the glistening stars reflected in her eyes. Light was not what she craved. It was only darkness in her heart that she let reign.

The darkness of the gods.

She breathed in deep. It was not yet time. She needed more information. She needed to see it for herself. In a month she would start her travels to the different bungalog in hopes of seeing her god.

Until then she would think of the wings and the whiskers, the blood red tongue and the mouth large enough to cast the world into terror.

One day she would use her powers to make it come alive.

One day.

=————————————————————————–=

Written by Karl Gaverza

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

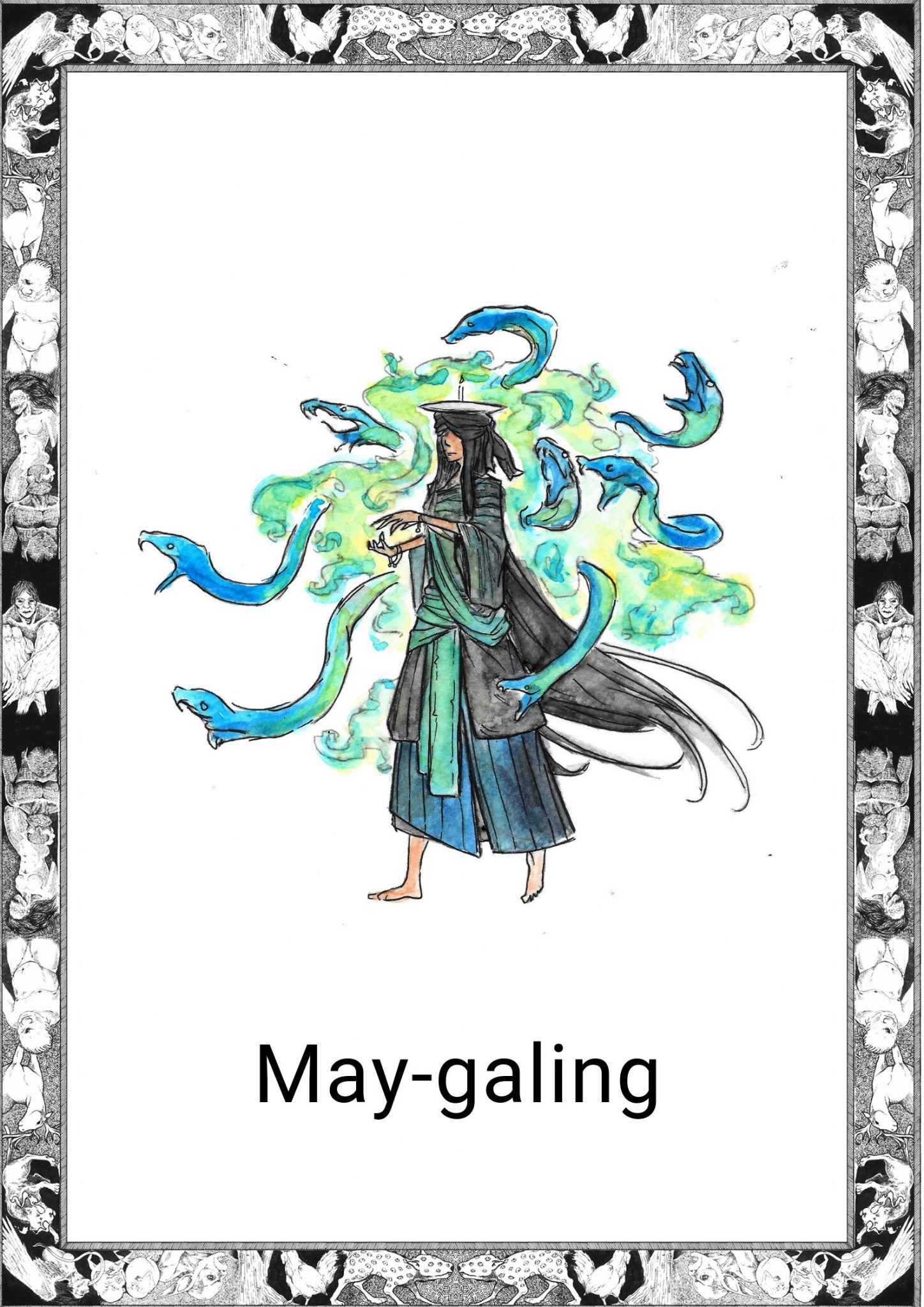

Inspired by the May-gling legends from Quezon Provinc and description in Diccionario mitológico de Filipinas in Volume 2 of Retana, W.E. Archivo del bibliófilo filipino by Ferdinand Blumentritt (1895), trans Marcaida D. (2019)

May-galing Illustration by Edrian Paolo T. Baydo

Color by Alexa Garde

Website: Lexa.us

More information on Philippine Snake species can be found in https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263375284_The_dangerously_venomous_snakes_of_the_Philippine_Archipelago_with_identification_keys_and_species_accounts