*Note this story is in Bisaya

Nahidamgohán kó na pud tó.

Nagkalúsnò ang siyúdad. Bag-óhay láng kó nakalíghot sa úmbok nga kánhi ang ákong baláy úg nagpanawág sa mgá sákop sa ákong bánay. Ámbot máy búhì pa ba níla. Gitán-aw kóng ákong mgá kamót, nagkadúgò silá sa paningkámot nákò og kinúykoy ádtong nalubóng ko.

Nagliróng nákò ang mgá syágit sa pakitábang sa ubáng tawö, pipíla níla lágmit mgá higála o silíngan kó. Bahálà silá, nagkasintó kó pagpangítà sa ákong bánay.

Únyà mitáy-og (na púd) ang yútà úg búgtong kóng madungóg ang syágit sa mgá tawö. Nagpangatúmba ang mgá póste sa karsáda ngádto sa gún-ob nang kabalayán.

Natúmba kó úg miapíl sa sinyágitay.

Únyà nakamatá kó, apán nagpadáyon ang dámgo. Dihâ kó sa ákong lántay, nagpangupót sa hábol, dúnay nagtán-aw nákò. Dúnay náa sa ákong tiilán. Naputôs sa daw mgá máta ang íyang láwas, tanán niíni nákò nagtútok.

Matág madamgohán kó kadtó, magpabílin ní og makariyô magtútok nákò, únyà makamatá kó daw waláy nahitabô.

Lahî karón.

Walâ pa gihápon kó makamatá.

Gitutókan kó sa maóng dámgo sa gatosán níya ka matá úg gilánsang kó sa ákong lántay.

Ámbot únsay íyang gústo, dílì man púd tingáli kadáot. Gilakángan kó niíni úg sámtang nagtútok kó sa nagpangídhat níyang láwas, sa katapósan nasábtan kó. Dílì diáy ní úrom. Úsa diáy ní ka pahimágnò. Buót kóng sugínlan sa daligmáta (ámbot ngánong nakailá kó sa íyang ngálan, kakuláhaw láng níng misantóp sa alimpatakán) arón púgngan kó nga mahitabô ang línog.

“Usáon kó man nâ pagbúhat?” gisunâ kó ang daligmáta. Súblì níng mitútok nákò. Kinahánglan kó adtóan kón diín ihimúgsò ang línog. Kinahánglan hangyóon nákò siláng magpuyô.

“Ngánong akó man?” Mibúhos daw búgwag sa kaamgóhan ang tubág sa ákong pangutána. Sa dámgo lámang nalaláng ang daligmáta, sa maóng kalibótan láng siyá naglihók, dílì siyá makaánhi sa átong kalibótan, ni makaduóng sa pinuy-ánan sa mgá línog úg mgá bágyo kón waláy kúyog nga magdalámgo.

Úg gikuyógan siyá og magdalámgo.

Dílì bayâ ingón kakuyáw ang pánaw sa gidahóm kó. Sa ákong húnàhúnà ang daligmáta nag-ingón nga damgóhon kó lámang arón mahidúlong kó úg túkmà ang íyang pagtultól. Gisúgò kó níya pagdámgo sa kalibótan apán dílì sa kón únsa sa nasáyran kó ní. Naghísgot siyá og gindaílan yútàng kalibotánon úg sa ilawóm niíni úg sa bukána sa mgá nilaláng nga nanimúyò niíni. Mitutalíyok sa ákong pangísip ang hulágway sa mgá bitín nga naglikós sa kalibótan úg gikúptan sa Magbabáya. Nadamgohán ko ang gindaílan, ang mgá bitín, ang Magbabáya.

Nadamgohán kó ang himugsoánan sa mgá línog. Nadamgohán kó ang kayutáan sa mgá hangín úg mgá bágyo.

Úg sa kakuláhaw dídto kó.

“O! kalibotánon.” Gitimbayâ kó sa babáyëng tíngog. “Matág kakitâ námò sa kamátang mo, ságad tungód júd sa Manglilíngla.” Miságbat ang laláking tíngog. Nakaámgo ísig ka úlo sa duhá ka higánteng bitín nga managsámang láyog pa sa kúhit-lángit. Malísang júd ángay úntà kó apán ang ílang katalahóron miághat nákò úg pagdáyëg. Gibátì kóng luwás ubán níla.Gitúklod kó sa daligmáta úg nahinumdóm sa ákong túyò. “Talahórong mgá Bitín…” Walâ kó kabaló unsáon silá pagtawág apán dílì man tingáli daotáng mopakítà og pagtáhod. Giasóyan kó silá sa bangúngot, ang kusóg nga línog nga migubâ sa siyúdad úg mitúmpag sa ákong baláy.”Dínhi ang pinuy-ánan sa mgá línog makalulúoy nga kalibotánon.” Mintubág ang laláking tíngog. “Búnga ang línog sa átong paglíhok.” Miságbat ang babáyëng tíngog. “Ang átong paglíhok maóy nagbugkós sa kalibótan.” Mitubág ang laláki. “Únsa pa may átong gamít kón magún-ob ang kalibótan?” Nangutána ang babáyë.”Kón matinúod ang ákong bangúngot, magún-ob ang ákong kalibótan. Oo, tipík láng ní sa katibúk-an sa kalibótan, apán kíng gamáy nga tipík maóy tibuók kóng kalibótan. Sáma kamahinungdánon níng siyudára nákò sa paghátag nínyo og bilí sa mgá kontinénte.” Maó tóy ákong tímpla.”May kaísog ka.” Pamúlong sa babáyë. “Walâ pay kalibotánong nakaprángka námò sa ingón niánà.” Mitubág ang laláki. “Ságad sa mgá kalibotánon moághat námò sa pagdáot sa ílang kaáway.” Mibalós ang babáyë. “Níndot níng kausãban.” Mitubag ang laláki. “Gisagònan mí sa pagpahilúnà sa kalibótan.”

Mitubág púd ang babáyë. “Nga púgngang mahitupáwak ang kalibótan.” Mibalós ang laláki. “Apán únsay áyo kón gún-ob ang katilíngban nga náa niíni?” Nangutána ang babáyë.

“Buháton námò ang gihángyò mo. Magpuyô láng mí arón dílì mapúsgay ang ímong kalibótan.” Nagdúngan pagpamúlong ang (duha ka) Intugbángol. “Paúlì na kalibotánon, dílì álang sa susáma nímo ang pinuy-ánan sa mgá línog.”

Buót kó úntà siláng pasalamátan, apán mihurós ang kusó nga hangín. Gipálid kó niíni úg hálos dílì na kó makaginhawá. Kusóg kaáyo ang huyóp daw murá kó og gilápa. Nakasínggit kó.

Úg akó nahigmatá.

Nagbágting na diáy ang ákong alárm. Alas syéte na sa búntag. Maulahí na júd kó sa kláse kón dílì kó magdalî. Trápik kaáyo rón, kadaádlaw. Nanghúy-ab kó, misúlay pagdúmdom únsa tóy ákong dámgo. Murá og dihâ tóy bitín úg dághang mgá matá mitútok nákò. Gawás niádto walâ na kóy mahinumdomán.

Mas lánog ang bágting sa ikaduhá kóng alárm. Sígnos ní sa pagsúgod taástaás kóng ádlaw.

Úntà may dághan pang kulbahínam kóng búhat

————————–

English Version

I had the dream again.

The city was dying. I had just managed to break loose from what used to be my house and I was screaming the names of my family members. I didn’t know if they were alive. I looked at my hands and I saw how badly they were bloodied from digging myself out of the ground.

All around me I could hear other people shouting for help, they may have been my friends or my neighbors. I didn’t care, I was too busy looking for my family.

Then the ground started to shake and all I could hear were people screaming. The posts around my street were falling one by one and smashing into the rubble of the houses.

I fall to the ground and my scream joins the chorus.

Then I wake up, but the dream isn’t over. I’m in my bed, holding my blanket and I’m being watched. There’s a thing at my feet. Its body was covered with what I guessed were eyes and it was staring at me with all of them.

Every time I had the dream It would just stare at me for a second and I would wake up like nothing ever happened.

This time it’s different.

I still haven’t woken up.

The dream stares at me with its hundred eyes and I stay frozen on my bed.

I don’t know what it wants, but I don’t think it means any harm. The creature walks over to me and as I stare at its blinking body, I finally understand. The nightmare wasn’t a nightmare at all. It was a warning. The daligmata (I don’t know how I know its name, it just popped in my head) was trying to tell me I needed to stop the earthquake from happening.

“How do I do that?” I asked the daligmata. It stared at me again, and I knew. I had to go to the place where earthquakes were born. I had to ask them to stay still. “Why me?” The answer to my question came in a flood of thoughts. The daligmata lives in dreams, and it can only move in that realm. It could never go in the physical world, much less the home of earthquakes and storms if it didn’t have a dreamer by its side.

And a dreamer it had.

The journey wasn’t as perilous as I imagined it to be. The daligmata was in my thoughts saying I only need to dream to be there and it guided me well. It told me to dream of the world, but not as I knew it. It spoke of the horizon, the split between the earth and the underworld and the mouths of the creatures that lived there. Images of the snakes wrapped around the world, held up by the great god Magbabaya, swirled in my head. I dreamt of the horizon, of the snakes, of Magbabaya. I dreamt of the place where earthquakes were born. I dreamt of the land of the winds and storms.

And in a flash, I was there.

“Hello mortal.” A feminine voice greeted me. “Whenever we see your kind Mangilala* usually has something to do with it.” A male voice answered back. I realized I was staring at the heads of two gigantic snakes, each bigger than a skyscraper. I would have been scared, but the majesty of the two was making me feel so much awe. I felt safe in their presence.

The daligmata nudged me from behind and I remembered why I was there. “Great Serpents…” I didn’t know how to address them, but I figured showing respect wouldn’t hurt. I told them about the nightmare I had, the giant earthquake that ripped through my city and shattered my home.

“This is the home of earthquakes, little human.” The male voice answered. “The shakes are caused when we move.” The female voice replied. “Our movements keep the world tethered.” Said the male voice. “What use are we if the world is gone?” The female voice asked.

“If my nightmare happens, my world would be gone. It may be a small part of the entire earth, but that tiny bit is my whole world. That city is as important to me as the continents are to you.” Was my answer.

“You are brave.” The female voice said. “No mortal has ever spoken to us with such candor.” The male voice replied. “Most mortals try to trick us into destroying their enemies.” The female voice answered. “This is a welcome change.” The male voice replied. “We are tasked to keep the world in place.” The female voice said. “To keep the earth from falling away.” The male voice replied. “But what good is that if a world within the world is broken?” The female voice asked.

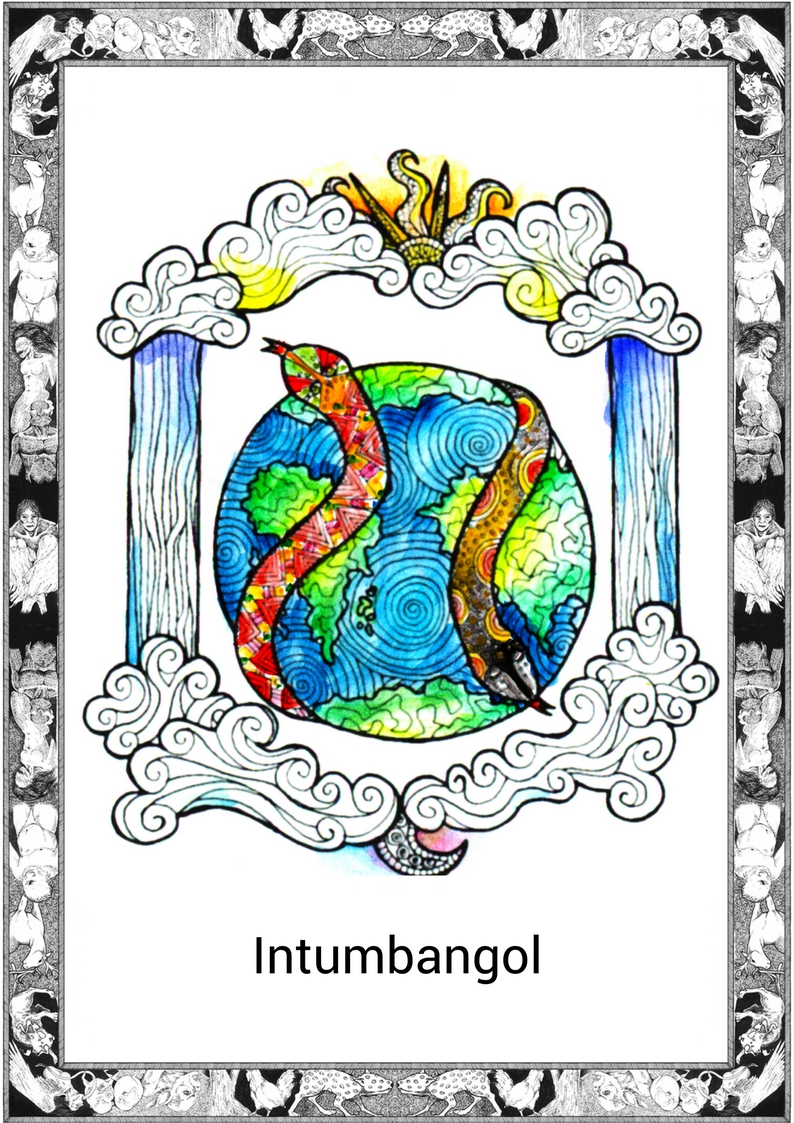

“We will do ask you ask. We will stay still so your world may be kept intact.” The Intumbangol replied in unison. “Go now, mortal. The home of earthquakes is no place for your kind to be.”

I tried to thank them, but a strong wind started blowing. It picked me up and I almost couldn’t breathe. The gusts were so violent I thought I was being ripped apart. I screamed.

Then I woke up.

My alarm was going off. It was 7 AM. I knew I would be late for class if I didn’t hurry. The traffic would be terrible today, like every day. I yawned and tried to remember the dreams I had. I think there was a snake and a bunch of eyes looking at me, but I couldn’t recall much past that.

My backup alarm rang even louder than the first one. It signaled the start of a really long day.

I wish I did more exciting things.

————————–

*Visayan (Bisaya or Binisaya) is a group of languages of the Philippines that are related to Tagalog and Bikol, all three of which are part of the Central Philippine languages. Most Visayan languages are spoken in the whole Visayas section of the country, but they are also spoken in the Bicol Region (particularly in Masbate), islands south of Luzon, such as those that make up Romblon, most of the areas of Mindanao and the province of Sulu located southwest of Mindanao. Some residents of Metro Manila also speak Visayan.

Written by Karl Gaverza

Bisaya Translation by Joseph Vincent (Josefwintzent) M. Libot

Copyright © Karl Gaverza

Translation Copyright © Joseph Vincent (Josefwintzent) M. Libot

Inspired by the Intumbangol description in The Soul Book. Demetrio, Cordero-Fernando 1991. And the Daligmata descriptions in Songs and Gifts at the Frontier : Person and Exchange in the Agusan Manobo Possession Ritual. Buenconsejo. 2002. & 101 Kagila-gilalas na Nilalang. Samar. 2015.

Watercolor by Tara Singson

IG: https://www.instagram.com/

Tumblr: http://

Watercolor by Alexa Garde

Website: www.Lexa.us

#PhilippineMythology #TheSpiritsofThePhilippine